Stars and Stripes marks 80 years of delivering military news that matters across the Pacific

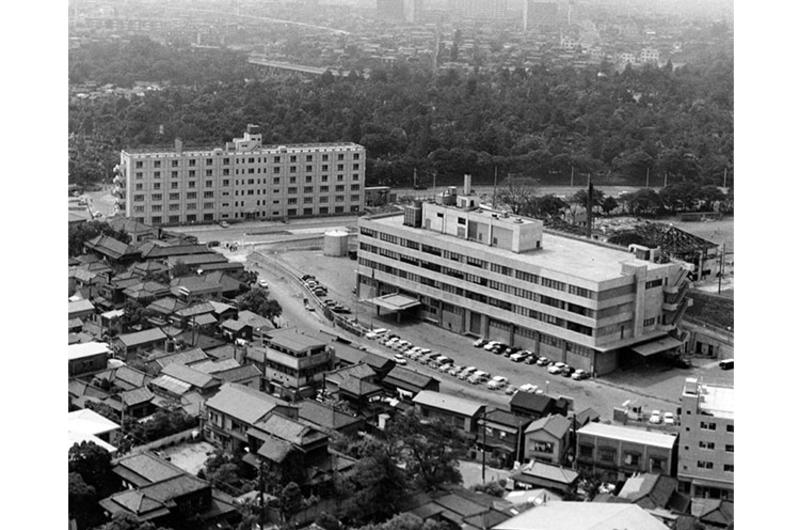

Birds-eye-view of the new Hardy Barracks office of the Pacific Stars and Stripes, taken after 1962. The newspaper moved into the new, four-story main office and printing plant - just a stone-throw away from its old office - on October 3, 1962.

By Joseph Ditzler, Aaron Kidd and Wyatt Olson | Stars and Stripes

TOKYO – For eight decades, Stars and Stripes reporters across the Pacific have covered wars, revolutions, natural disasters and the political changes that marked turning points for the United States and its military overseas.

As Philippine bureau chief for Stars and Stripes’ Pacific edition in 1991, Susan Kreifels experienced firsthand the eruption of Mount Pinatubo, which hastened the U.S. exit from its military bases in the island nation.

“I kept thinking we’d be dug up one day just like the people in Pompeii,” Kreifels said. She and her driver stuffed a car full of refugees in an Angeles City barrio in a blizzard of volcanic ash.

“This stranger pushed a crying baby through the window into my lap and disappeared,” she said. “Can you understand the fear that would cause someone to give a baby to a stranger?”

The Philippine chapter marked just one in the long American experience in Asia. Just as journalists from Stars and Stripes witnessed that change, they have been present for momentous events since May 14, 1945, when the first Pacific edition rolled off the press.

Born in the late stages of World War II in the Pacific, the “soldier’s newspaper” lived up to its name. Its front pages brought the big-picture news to the troops in the field, while the inside pages told the stories of those same soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines.

From World War II, the occupation of Japan, the Korean War, Vietnam, the long wars around the fight against terrorist organizations down to the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan, Stars and Stripes was present as events unfolded.

Brian Brooks, the former associate dean for the School of Journalism at the University of Missouri, spent two years as editor of Stripes’ European edition. He also served as an Army public information officer during the late stages of the Vietnam War.

Brooks remembers troops in Vietnam and Bosnia emptying the racks of newly arrived Stars and Stripes newspapers and sharing them among themselves, six or eight to a paper.

“The most important thing to me about Stars and Stripes is it is an example to the rest of the world of how open we are as a society in the United States,” he said. “What other military in the world publishes a newspaper that the commanders don’t control the content of? It’s unheard of. I think it’s a great example of press freedom and what we stand for as a country.”

‘Every man’s role’

The first Stars and Stripes Pacific edition – eight pages – was produced in Honolulu, where the military newspaper shared office space with the Honolulu Advertiser and wire services with the Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

War news dominated the front but inside pages carried an array of features, sports and entertainment. The Brooklyn Dodgers were on an 11-game winning streak that month. Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall were about to wed, and actor Boris Karloff and playwright Moss Hart appeared with an “all-soldier cast and band” in a USO Camp Show on Saipan, only a year earlier a stage for vicious combat.

The war in Europe had concluded but the fight in the Pacific grinded on. Stars and Stripes told that story, often in tones that reflected the grim and callous nature of the 3 ½ -year-old conflict.

The United Press in that first edition reported a daylight raid on Nagoya, Japan, by 500 B-29 Superfortress bombers that dropped 3,500 tons of incendiaries – 40 tons every minute for 90 minutes.

“A couple more like that and you can scratch that town off your list,” the news service quoted Col. Carl Storrie of Denton, Texas, as saying.

Meanwhile, the fight for Okinawa was underway, and Stars and Stripes reporters were there. The writing reflected the tenor of the times. The Japanese enemy was routinely referred to in terms regarded today as offensive. Stories often focused on killing and survival.

Staff writers surveyed Pacific combat veterans for advice on fighting the Japanese that they’d share with Europe theater veterans expected to arrive for the final push on Japan.

Stars and Stripes staff writer Pfc. Bill Land profiled Staff Sgt. Jon Freeman of Arkansas, also known as “Killer” Freeman, who had single-handedly sent 27 enemy soldiers to their deaths during six weeks of combat in Leyte, Philippines.

Land’s photograph of Freeman captured the image of an American fighting man in the final stages of the war. A cocked steel helmet shadows the right side of his face, a cigarette angles down from the corner of his mouth, his left eye focuses on something to to his right. He cradles his rifle in his arms across his midsection. Three grenades hang on his field jacket on either side of his chest.

Killing the enemy was Freeman’s hobby, according to a headline. “Shoot him from the belly up,” was his advice to the newcomers.

Winning a ‘feverish race’

The outlook changed on Aug. 6, 1945, although the page 1 story out of Washington, D.C., by United Press, in retrospect, left questions unanswered. An atomic bomb “with power equal to 20,000 tons of TNT,” had been dropped on Japan.

The story identified Hiroshima as the targeted city and divulged that the U.S. had won a “feverish race” with German scientists to harness atomic power.

The front-page headline on Aug. 7, 1945, revealed more information and strode across six columns: “Report Atom Toll Heavy,” with a smaller headline indicating the city was wrecked beyond Japan’s ability to immediately comprehend.

A Stars and Stripes editor, Cpl. Anthony Kott, summed up news of the first atomic bombing. “The atom bomb continued to pale all other news into insignificance in the States,” he wrote, “as the American public was heartened by prospects of a shorter war but was awed by the bomb’s implications.”

Two days later, news arrived of a second atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki. Played just as prominently was word that Soviet troops had made their first moves against Japan. Both developments signaled the conflict’s end.

A roundup of reports carried the headline, “Nagasaki Resembles Volcano Still Afire, Says Eyewitness.”

A week passed before a banner headline on Tuesday, Aug. 14, 1945, in flowing typeface heralded “Peace” above the news: “The Pacific war ended Tuesday — 1,347 days after the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor.”

The first Stars and Stripes staffers to report from Japan’s main islands did so from air and sea Aug. 28-29, 1945.

Cpl. Davis wrote from Okinawa of riding aboard one of the final B-24 bomber combat missions over Kyushu and Shikoku. Other than flying over what had been recently the enemy homeland, the flight was routine, he wrote. Davis looked down mostly on rice paddies, terraced slopes and empty roads, he reported from the “recon mission.”

Tech Sgt. Dick Koster wrote from the USS Gosselin on Aug. 29 that Japan’s naval base at Yokosuka, today home of the U.S. 7th Fleet, looked “desolate and ghostly.” He described the battleship Nagota, crippled by American air attacks; sunken or beached barges; and white flags dotting the hillsides marking gun emplacements.

With the war’s end near, the news turned to the coming post-war economy and the nation’s capacity to absorb the discharged veterans coming home to the labor force.

The American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars demanded improvements to Veterans Administration hospitals “to avert an imminent breakdown,” the paper reported June 12, 1945.

A United Press report quoted a psychiatrist warning of the effects of combat on returning veterans. What today is called post-traumatic stress disorder would result in higher rates of alcohol abuse and alcoholism.

Less than four months later, Stars and Stripes started publishing from Tokyo. The first Pacific edition rolled off the presses of the Asahi Shimbun on Oct. 3, 1945. The newsroom and other offices were several blocks away at the Nippon Times (now the Japan Times).

The newspaper remained there until 1952, when it moved to the Hardy Barracks compound, also in Tokyo, a former Japanese infantry base. In 1962, the paper relocated to a new structure on those grounds, the Akasaka Press Center, where its Pacific offices and printing press remain today.

‘Korea At War’

Pacific Stars and Stripes delivers news as it happens. It did so June 25, 1950, when a page 1 headline declared “Korea At War” on the same day North Korean troops poured over the 38th parallel “with tremendous power at 5 a.m.,” according to a wire report.

Several editions rolled off the press that day, and subsequent days, as events in Korea unfolded. The front page carried big-picture stories about the unfolding conflict posted mostly by civilian reporters for The Associated Press, United Press and International News Service.

Stars and Stripes staffers found the local angle in the conflict, whether frontline accounts of battle action; high-level meetings in Tokyo between Gen. Douglas MacArthur and government officials like John Foster Dulles, foreign policy adviser to the State Department; or rear-echelon events, like jazz singer Al Jolson performing in Tokyo for wounded soldiers.

The war news at first was grim as North Koreans cornered U.S. and South Korean forces inside the Pusan perimeter from August until early September. While U.S. B-29 bombers lashed North Korean troops, allied units strengthened defensive positions.

MacArthur turned the tide by sending waves of Marines ashore Sept. 15 at the port city of Inchon, behind the North Korean lines and at the doorstep of Seoul. Wire services kept the troops abreast of the big picture.

Meanwhile, Pacific edition reporters with the grunts reported action at the front. Cpl. Bobby Rushing wrote how medical officer Capt. Melbourne Chandler led a surrounded 1st Cavalry Division battalion to safety after four days of heavy fighting. The battalion commander was killed, leaving Chandler in command.

The unit came under tank and automatic weapons fire from the “Reds,” or North Koreans, Chandler told Stars and Stripes.

“We couldn’t move in any direction as they were firing right down our throats,” he said.

The same day, a front-page story with a three-deck headline delivered some good news from general headquarters in Tokyo: “Men at the Front Will Have Beer.”

The northward push by the U.S. X Corps brought them to battle with forces sent by China to push the allies back into South Korea. They met at Chosin Reservoir in the final, cold months of 1950.

Stars and Stripes reporters with the Marines and Army units of X Corps filed delayed accounts of the battle that became U.S. military lore. Holding out against repeated assaults, U.S. troops battled their way out of the high, frozen plateau in December.

“Grace of God, Courage of GIs Enables Escape” was the headline on an account by Sgt. Connie Sellers with the Army’s 2nd Infantry Division that appeared Dec. 17, 1950. He wrote how Capt. Lincoln Wray led his 300 men from a death trap to eventual safety.

“By this time, we had walked for 16 hours and about 40 miles through rugged mountain ridges. The men were tired out, but determined not to be trapped and captured,” Master Sgt. Jerry Grafton said in Sellers’ account. “We by-passed the machine guns and kept going.”

Another account from the X Corps told how Army and Marine engineers repaired a tortured, impassable, 20-mile-long stretch of highway and gave allied troops an escape route from the Chosin Reservoir.

“Craters were filled, a vital bridge twice rebuilt after infiltrating enemy troops cut it and dozens of roadblocks of timber, brush and blasted vehicles cleared,” said the Stars and Stripes report.

The war raged across the Korean Peninsula nearly three more years. On Monday, July 27, 1953, the troops read in Stars and Stripes Pacific the news they’d long awaited: “Fighting Ends Tonight.”

Inside, Pfc. Tony Ricketti reported from Panmunjom, the village where documents were signed instituting an armistice that remains in place today.

“Even as the signing took place mortar rounds could be heard in the distance and American jets struck a bit further off,” Ricketti wrote that day.

A golden era

As the Korean War drew to a close, events in the French colony of Indochina in Southeast Asia set the stage for U.S. involvement there.

The Vietnam War, which for U.S. combat troops lasted from 1965 to 1973, ushered in what some regard as a golden era for the paper.

“They did really robust reporting from ’67 to ’69,” said Cindy Elmore, a journalism professor at East Carolina University who has published scholarly articles examining command influence and censorship of the newspaper.

During that period, the Pacific paper’s top editor was Col. Peter Sweers, a World War II veteran and Bronze Star recipient who held a bachelor’s degree in journalism.

“He was very supportive of freedom of the press and of treating Stripes just like any newspaper covering the Vietnam War,” said Elmore, a Stars and Stripes reporter in the late 1990s.

The newspaper also benefited from a wide swathe of talented draftees, some of whom had Ivy League degrees or actual journalism experience back in the States, Elmore said.

“We aggressively went out and covered stuff, and the military didn’t much like that,” said Robert Hodierne, a reporter and assistant editor at the Saigon bureau in the late 1960s.

Many would go on to illustrious journalism careers, such as Jack Fuller, who earned a Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing at the Chicago Tribune, and Steve Kroft, for 30 years a correspondent with “60 Minutes” before retiring in 2019.

“It’s probably the best job I ever had,” said John Olson, a staff photographer whose work quickly led to a position at the prestigious Life magazine.

A 19-year-old draftee longing to shoot photos for Stars and Stripes when he arrived in Vietnam in 1967, Olson commandeered a jeep and made an unauthorized trip to the newspaper’s office in Saigon. The paper pulled some strings and took him aboard after he embellished the scope of a former mailroom job with United Press International.

The first combat assault he covered was Operation Billings in June 1967, where he talked himself onto the second wave of helicopters heading to the landing zone – air shaking with artillery and a napalm inferno below.

Olson had brought his camera to a particularly hellacious two-week operation that took the lives of 57 Americans.

“But I didn’t know any better,” he said. “I thought this was just another day at work.”

He would not see that kind of intensity again until the Battle of Hue in February 1968, one of the longest and bloodiest of the war. Marines waged an inch-by-inch assault to take the well-fortified Citadel from dug-in North Vietnamese troops.

“I went in there with, I think, 19 rolls of film, and I stayed until I shot every exposure I had,” Olson said. “It was violent. It was upfront. It was personal.”

Getting that film published in a timely manner was no small feat because unlike the wire services covering the war, Stars and Stripes had no in-country darkroom. Hodierne recalled how film had to be brought to Saigon and then put on one of two Boeing 737 planes chartered by Stars and Stripes that flew a Pacific circuit delivering newspapers printed in Tokyo.

“So, if we shot pictures on the field on Monday – if everything went just right – that film could be in Tokyo on Tuesday and be in Wednesday’s paper,” Hodierne said.

‘A hellish nightmare’

The U.S. military’s role in world events took a breather after the Vietnam War but history rolled on through civil unrest against authoritarian states in South Korea, Iran, the Philippines and elsewhere, places that presented new challenges to the United States.

Few nations experienced the scale of change that took place in the Philippines when a popular revolt in 1986 unseated President Ferdinand Marcos, a corrupt and authoritarian ruler who held sway in the island nation for 20 years.

Events following Marcos’ departure and the election of Corazon Aquino had deep implications for the U.S. military presence there, symbolized primarily by Subic Naval Base and Clark Air Base.

Susan Kreifels worked from Clark as a Stars and Stripes bureau chief from 1987 to 1991 – the first woman to hold such a position for the newspaper. Afterward, she moved to Tokyo, where she worked as Japan bureau chief for another four years.

“I always wanted to be a foreign correspondent,” she said. “Stripes gave me that opportunity.”

Before the Pinatubo eruption that changed the course of U.S.-Philippine relations, Kreifels covered a series of attacks that claimed 10 American lives. A group of communist insurgents, the New People’s Army, killed several, including two airmen and a retired Air Force officer outside Clark in 1987 and an Army colonel in 1989.

For Kreifels, reporting on the series of politically motivated attacks was the most important story she covered in her 10 years with the newspaper.

“My editors and I felt we had a responsibility to let our military readers know the real dangers outside the bases,” she said, “and understand what was going on in the country.”

A May 1990 article in the wake of two more airmen shot dead interviewed locals whose livelihoods depended on the American presence. Travel off Clark by members of its community was restricted.

A tricycle driver said his income was halved as a result. Another Filipino expressed hatred of the Americans. “We don’t need the bases,” he said.

Mother Nature soon obliged. Mount Pinatubo, which loomed over Clark, erupted June 12, 1991, after simmering and shaking since April. The explosion instantly disintegrated 900 feet of the summit and blanketed the surrounding area in ash and mud.

Kreifels wrote first-person accounts of the ongoing eruptions and their aftermath. Under a headline, “Scenes from a hellish nightmare,” she reported June 17, from Angeles City: “It is difficult to describe the hellish nightmare that 40,000 troops, wives and children are now living in the Philippines. Ash and rocks are covering us, spewed from a volcano in our backyards.”

The next day, still working her beat, Kreifels wrote of sleeplessness and the apocalyptic landscape in which the survivors felt somehow damned. She recalled meeting Air Force Staff Sgt. James Nelson and two other sergeants along a roadside in a broken-down Jeep.

“They gave me a wet, crumpled note to get their names to their commander,” she wrote. “Fatigue and fear were on their faces as they tried to reach the evacuation site.”

The Pinatubo eruption brought the curtain down on the U.S. presence at Clark and Subic Bay, but Stars and Stripes Pacific continues to cover the intersection of Philippine and U.S. military interests to this day.

‘Don’t ask, don’t tell’

Military campaigns in the Balkans and the Middle East dominated war planners and Washington, D.C., during the 1990s, and Stars and Stripes covered the Persian Gulf War and the conflict that engulfed the former nation of Yugoslavia. But the Pacific was no backwater in terms of military journalism.

On Nov. 2, 1992, a short item on page 6 of the Pacific edition identified a sailor from the USS Belleau Wood whom the Navy said was beaten to death by two shipmates in a park outside Sasebo Naval Base, Japan.

Rick Rogers, at the time an Army sergeant and Stripes reporter in Tokyo, was assigned to follow the story by an editor who had received a letter from others at Sasebo alleging the sailor, Seaman Allen Richard Schindler, was targeted because he was gay.

Being gay in the military is no longer a crime, but at the time a transitional policy, “don’t ask, don’t tell,” was in effect.

“It took a long time to get that story out,” said Rogers, now a financial adviser in San Diego. Schindler was killed in October 1992 but not until December did the Navy admit his death may have been linked to his being homosexual, “which turned out to be the case,” Rogers said.

“I was an E-5 trying to hold admirals’ feet to the fire, and commanders, to give up information. Not the easiest thing in the world,” he said.

Rogers, who went on in civilian life to cover the military for newspapers in Virginia and California, said he learned two professional lessons as a Stars and Stripes military staffer.

One, don’t give up, “because then they win,” he said. Two is do nothing untoward. Press the authorities, hold them accountable, but do it the right way. “You have to be 100% right on everything,” he said.

Stars and Stripes provides a perspective no other medium can provide, Rogers said, adding it’s the only source of news military service members, their families and others connected to the services have on some issues.

“It’s not the type of information they’re going to get elsewhere,” he said.

The military hierarchy benefits from Stars and Stripes, though it often works to frustrate its coverage, Rogers said. The newspaper shines light on problems that can be resolved before they escalate into congressional inquiries. The newspaper, he said, is a kind of loyal opposition.

“I was never interested in tearing down the military. I think the military is an outstanding institution, in general,” he said. “That doesn’t mean it’s a perfect institution. I saw my job as helping make things better.”

‘Sprung into action’

In early September 2001, Stars and Stripes Pacific reported on Defense Department plans to close military bases, a move that Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld said was necessary to save money for other uses. Within a day that view suddenly seemed outdated.

The Sept. 11, 2001, edition, published while terrorist attacks on the U.S. were still the better part of a day away, led with a story about the trial of an Air Force staff sergeant for alleged rape. U.S. military bases around Tokyo braced for a typhoon and Marines pitched in to help fight a fire on a small island off Okinawa’s coast.

Kathleen Guzda Struck, at the time Stars and Stripes Pacific’s managing editor, was at home that evening in Tokyo watching TV when a bulletin appeared on-screen. A plane had struck the north tower of the World Trade Center in New York.

“As I was sitting, watching it, the second plane went in,” she said.

The newsroom in the Akasaka Press Center that night was a beehive, Struck said. She arrived to find everyone at the paper had returned to start working on the story.

“People had just sprung into action, trying to figure out what’s going on,” she said. “The active-duty journalists were always amazing, incredibly well-trained. I loved working with them. Of course, the civilians were, too, but the active-duty staff probably understood on a different scale what was happening.”

From that day on, Pacific edition pages were filled with reports connected to America’s response, military and otherwise, to 9/11. The tone changed. Topics shifted from downsizing military facilities and a slumping economy to the movement of forces from the Pacific and questions of security for service members and their families.

Stripes surveyed its readers and gauged their sentiments, as well. In October 2001, a headline indicated U.S. military and civilians supported the U.S. strikes in Afghanistan in response to the 9/11 attacks. “America did ‘what we had to do,’” the headline said.

Meanwhile, Stars and Stripes journalists based in the Pacific were dispatched along with their colleagues from other bureaus to cover the invasion of Afghanistan and, in 2003, the invasion of Iraq. Stars and Stripes had a head start in some ways but was caught unprepared in others.

“Not all of our Stripes journalists were accustomed to covering conflict and the [Department of Defense] was kind of scrambling to figure out what their role was, so for instance, that’s when embedding really started for all news outlets not just military,” Struck said.

Journalists from the civilian world were finding their way into the military environment that Stars and Stripes journalists know well. Their organizations – broadcast networks and big-city daily newspapers – could afford to train their employees for combat situations, including exposure to live fire or possible kidnapping.

But Stripes journalists knew their way around military bases and how to work with DOD personnel.

“One of the most amazing things about Stars and Stripes to me was, even though we were independent journalists, we all carried ID cards that would allow us onto any military installation,” Struck said. “So, while we’re walking through the gate trying to find Col. So-and-So or Lt. Col. So-and-So or whomever, our commercial colleagues were having to catch up.”

‘Lifted out of the sea’

The new millennium only started with 9/11; it continued to present fresh challenges to Stars and Stripes Pacific. Natural disasters would figure prominently in the newspaper’s coverage. Reporters and photographers were dispatched to see firsthand how the U.S. military switched from combat mode to disaster relief.

In December 2004, a magnitude 9.1 earthquake off the island of Sumatra, Indonesia, gave rise to a devastating tsunami, 30 feet high in some places where it came ashore. The series of waves killed about 225,000 people, as many as 200,000 in Indonesia alone.

Stars and Stripes Pacific reporters documented the relief effort by U.S. military units stationed on the main islands of Japan and on Okinawa. From Yokota Air Base in western Tokyo, Air Force flight crews logged 2,500 hours and hauled 4 million pounds of humanitarian aid to affected areas in four countries, Stripes’ Vince Little reported in 2005.

Another Stripes journalist, Juliana Gittler, reported from Thailand on the work approximately 15,000 U.S. service members undertook to provide relief as well as rebuild some areas swept away by the tsunami.

“They carried food, drinking water and medical aid to remote locations, removed debris and helped to identify remains of people lost in the disaster,” she wrote a month after the quake.

Six years later, reporters and photographers responded to another disaster, this time closer to their home away from home.

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.0 temblor, the Great East Japan Earthquake, followed by a tsunami that came ashore 90 feet high in some places, crushed the Pacific coast of northeastern Japan.

The tsunami inundated an area up to six miles inland in places and when its waters swept back to sea it took 5 million tons of material and debris with it. Ultimately, as many as 20,000 people were declared dead or missing because of the combined disaster.

Complicating matters, the tsunami knocked out generators at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, causing cooling systems to fail and precipitating a partial meltdown of the fuel core. Hydrogen gas in the outer containment buildings exploded, releasing radiation into the atmosphere. Seawater leaking from the plant became contaminated.

In response, the U.S. military launched a relief and reconstruction effort dubbed Operation Tomodachi that lasted six weeks and involved 24,500 service members at its most intense. Tomodachi is the Japanese word for friend.

Stars and Stripes rotated reporters and photographers in and out of the affected area during the operation. They documented not only the relief effort, but also the stories of survival told by dozens of Japanese citizens living in temporary shelters.

Veteran reporter Seth Robson had only recently arrived in Tokyo from his previous post in Germany when he saddled up with Nathan Bailey, a photographer and military staffer, and Elena Sugiyama, an English-speaking Japanese librarian who pitched in as a translator.

“I’ve been to half a dozen major disasters for Stripes and this was the biggest in terms of damage,” Robson said. “My first impression, it was amazing to see massive ships, including a container ship, lifted out of the sea, to see probably hundreds of cars just wrecked by the flood, even fishing boats and commercial boats in the street.”

The reporting team set up shop in the city of Sendai, hard hit by the tsunami.

“We were living on MREs,” Robson said. “There was a major aftershock, a really heavy quake, it actually killed people. I remember thinking I might run outside the house, but I remember thinking the other people might think I abandoned them.”

Sugiyama logged about a month on reporting trips, going back and forth to the disaster zone.

“What we saw when we first got there was devastating,” she said. “It was nothing that I even imagined.”

Robson, Sugiyama and Bailey met a family doing its best to clean up its business, a small bar. What struck Sugiyama was how positive they were. Their attitude amid so much destruction touched an emotional chord.

“They were just doing what they had to do,” she said. “The more I think about it, I kind of choke up. That’s when I realized what I was getting into. I just can’t get emotional in front of these people, that’s not what they want to see.”

The hardest part of her experience was approaching a woman looking for her missing sister in a temporary morgue in a gymnasium.

“I really didn’t want to do it,” she said, “but I knew that was my job, to do that. I forced myself to do that.”

The woman didn’t find her sister, but Sugiyama gave her information on other sites where bodies were collected. The woman was grateful for that information, which gave Sugiyama some comfort knowing she’d helped in some way.

“It was a horrible thing that happened, but it was a great experience for me to be able to work with the journalists,” she said. “It gave me a better understanding of what Stars and Stripes is all about.”

Enduring legacy

The newspaper faced an existential crisis in 2020, when budget cuts and a proposal to eliminate funding cast doubt on its future.

Public outcry, bipartisan support from lawmakers and the dedication of its staff ensured its survival. The episode highlighted the enduring importance of independent military journalism and Stars and Stripes’ vital role in informing service members around the world.

Meanwhile, a once-in-a-century pandemic crept across the world, complicating the U.S. military presence in the Indo-Pacific.

Stars and Stripes reporters rose to the challenge, documenting the military response and tense relations with host countries as COVID-19 claimed hundreds of lives and forced millions into seclusion.

Reporters brought readers an exclusive interview with a 23-year-old soldier at Camp Carroll, South Korea – the first U.S. service member infected with COVID-19 in February 2020.

The following month, they covered the first active-duty service member to die of the disease – a 41-year-old chief petty officer aboard the USS Theodore Roosevelt. The outbreak on the aircraft carrier, which was diverted to Guam, led to the removal of its skipper and the resignation of the Navy secretary.

As the pandemic subsided, Stars and Stripes reflected on lessons learned, exploring changes in relationships with America’s allies, adversaries and host countries, as well as the pandemic’s effects on the U.S. economy and military readiness.