War forced hard choices for those who fought and those who did not

Rep. Alexander Pirnie, R-NY, draws the first capsule in the lottery drawing held on December 1, 1969. The capsule contained the date September 14.

By Chris Carroll | Stars and Stripes November 11, 2014

WASHINGTON — Millions of Americans in the 1960s and early 1970s had to decide what they would do when called to serve in a conflict that had mushroomed into the most polarizing event in the nation’s history since the Civil War.

Among them were three young men forced to make choices that would reverberate through the rest of their lives.

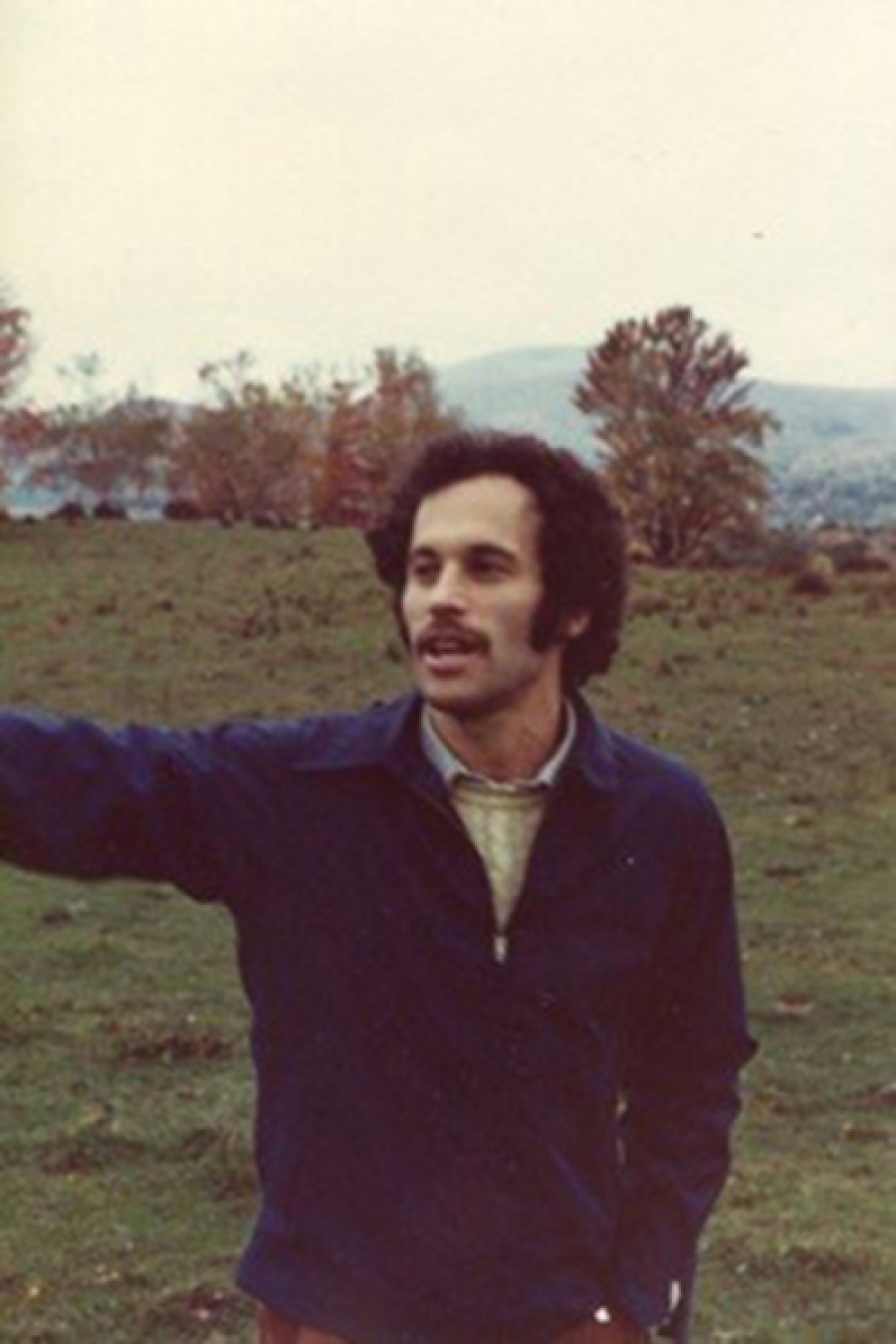

Moral opposition to the war and the fear of pointless violence drove Tom Weiner to pull strings in order to avoid conscription. But his realization later that he’d essentially sent a poorer American to fight in his place has haunted him ever since.

John Sibley Butler, born into a southern family with a history of military service, never considered dodging the draft. The Army became a stepping-stone toward a successful academic career for the decorated veteran.

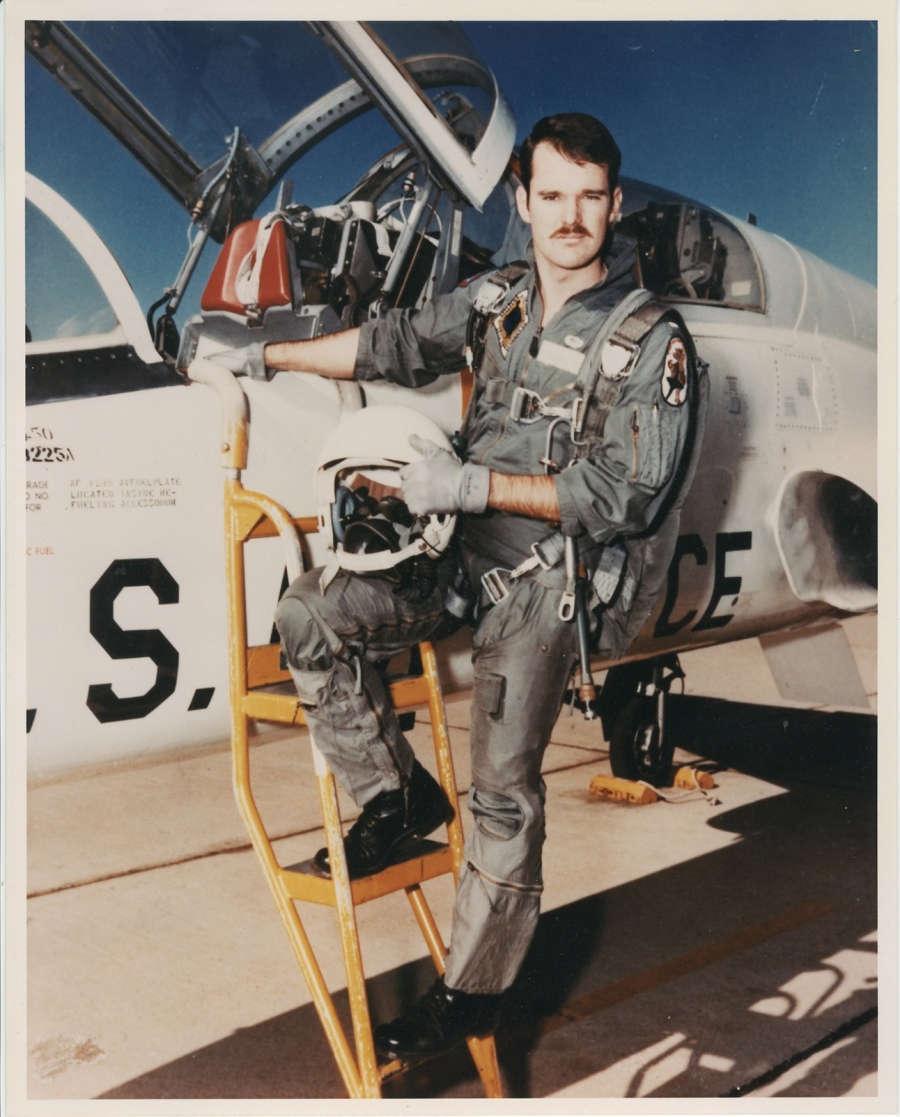

For Charlie Clements, patriotism compelled him to drop out of a plum spot in graduate school and volunteer for Vietnam. Once there, pangs of conscience over the war’s conduct would eventually plunge him into crisis.

Though the stories are individual, the questions the three faced in the age before today’s all-volunteer military were universal.

Some young Americans went to extremes, becoming war heroes or leaders in protest movements. Young men, some not yet old enough to vote, faced off against a determined and fearsome enemy in Southeast Asia, while peers publicly refused and faced jail in the United States. Tens of thousands left their lives behind and hightailed it to Canada. Most sobering of all, more than 58,000 Americans gave their lives in Vietnam.

But for every military-age American man who took a definite stand in support of or against the war, statistics show that a larger number managed to walk a middle ground. Out of about 9 million troops on active duty between the Gulf of Tonkin incident in August 1964 and the “official” end of the war in May 1975, as declared by President Gerald Ford, only 2.7 million actually set foot in Vietnam, according to Department of Veterans Affairs statistics. Most of the rest, by chance or determined effort, were assigned outside the combat zone.

There were other ways to avoid fighting in Vietnam for those — like a pair of recent U.S. presidents — who were able to take refuge in National Guard units or university study. Student deferrals, however, depended on decent grades, and graduation threw former students back into the pool of eligible draftees.

TOM WEINER

In a bid to quash complaints about the unfairness of the draft, the first Vietnam draft lottery was held Dec. 1, 1969. One by one, capsules containing a date on a slip of paper — one for each day of the year — were pulled from a glass jar, determining the order that young men born between 1944 and 1950 would be conscripted. The first date drawn was Sept. 14, meaning those born on that date would be the first drafted under the new system.

One of countless Americans waiting in agony for the results was Tom Weiner, then a student at Trinity College, a private liberal arts university in Hartford, Conn. When his birthday, Oct. 22, was drawn relatively early in the proceedings, he felt sure he would be in Vietnam soon after his 1971 graduation.

“I immediately knew unless the war somehow ended before I graduated, I was going,” Weiner said in an interview.

Weiner, a frequent participant in demonstrations against what he saw as an unjust war of aggression by the United States, unsuccessfully applied for conscientious objector status, and meanwhile began to see a host of doctors to document every possible physical problem that might disqualify him.

With advice from a draft counselor his parents had hired, Weiner documented back problems, calcium deposits on his feet, mental health issues. At his physical exam, however, none of his claimed problems disqualified him from service.

“I knew what was coming, so I’d done a lot to prepare,” he said. “The problem was, none of it worked.”

Sure that induction was imminent, Weiner had one more appointment — with an Army psychiatrist to discuss his alleged mental health problems. But instead of a discussion, the man simply asked him two question: Had he ever used illegal drugs, and had he ever fantasized about suicide?

The sensitive liberal arts student answered yes to both questions, and was immediately disqualified from the draft with the words “drug abuse” scrawled on a form.

“I have no idea why he asked those questions — maybe there were some guardian angels there for me,” Weiner said.

He walked out relieved, passing through a room of other men waiting for their physicals — largely working class African-Americans. None appeared to have appointments lined up with the Army shrink.

Concerned about the effects a drug abuse designation could have on his future employment, he discussed it with his draft counselor, who assured him, “Don’t worry, you’ll be a hero because of this.”

He didn’t feel like a hero as he moved on with his life, becoming a teacher. He continued to be haunted, knowing that he had avoided what men from lower economic strata could not.

“It was purely a result of my privileged position in society I’d even been able to get that appointment in the first place,” he said.

His discomfort eventually drove him to collect dozens of stories of Vietnam veterans and resistors for a 2011 book, “Called to Serve.” The stories delve into why people chose to serve or refused, and what the effects of their decisions were.

“To be 18 or 19 and asked to make a life or death decision — concerning your own life and the lives of many others — it’s just an incredible thing,” he said.

JOHN SIBLEY BUTLER

His forebears had served, and John Butler would too.

“If you looked back at World War I and World War II, it seemed like every generation had its war,” he said. “My attitude was, ‘It’s about time for me to serve,’ and that’s what I did."

Drafted soon after graduation from Louisiana State University, Butler entered the Army along with many of his classmates. As southerners, they did so with little fuss, he said.

But in other parts of the country, black students like himself were increasingly protesting the war, moved by the message of Black Power and questioning what part African-Americans had in a Southeast Asian war.

In fact, Butler said, they played a big part. As fighting accelerated between 1965 and 1969, black troops suffered a disproportionately high rate of combat deaths, as he would document decades later in his contribution to the “Oxford Companion to American Military History.”

It was a sacrifice of blood that helped African-Americans reach a place of greater opportunity and equality in the U.S. Army than in nearly any other part of American society, said Butler, now a professor of management at the University of Texas-Austin, and a consultant to the U.S. military and industry.

“We call that an ironic step forward,” he said. “Black soldiers literally had to fight to fight — while everyone else is trying to dodge the draft, I might add.

“It was the first time black soldiers had been able to break down that barrier since the Revolutionary War,” Butler said. “It was the first time in almost 200 years they had literally fought side by side with white soldiers.”

A medic stationed at a surgical hospital at Chu Lai Air Base, Butler was awarded a Bronze Star with a “V” device for his conduct a situation he’ll only say “involved a lot of people wounded in some pretty awful circumstances.”

He left the Army as an E-5 as soon as his term of conscription ended, ready to continue his management studies. Advised against wearing his uniform in the United States as prepared to process out, he instead wore it more frequently than necessary, daring those who’d refused to serve to make an issue of it.

“With all that was happening, you had all these white kids dodging the draft up in Canada,” he said. “If you want to burn my ass, talk to me about the forgiveness they received in the form of a presidential pardon.”

“Yes it was the right thing to do,” he said. “But if all those kids had been black, they never would have received it.”

CHARLIE CLEMENTS

While some of his classmates at the Air Force Academy were fighting and dying over North Vietnam in 1968, Charlie Clements was settling into graduate school at the University of California-Los Angeles, where the Air Force had sent him for a business degree.

Clements was an avid supporter of the Vietnam War, and seethed with contempt for draft resisters. His plan was to do his part in the war upon graduation.

But as he prepared to join a UCLA graduate business fraternity in 1968, he realized that he and the other conservative, well-off young men in the fraternity weren’t contributing any more to the war effort than the draft resisters they loathed.

“It was really quite interesting that no one except me in this business fraternity had any intention of serving or going to Southeast Asia,” he said. “These were young men in business school, who like Vice President Cheney, supported the war but were content to let others go to fight it.”

Deep cultural differences divided Clements, the son of an Air Force officer, from his new classmates in California.

“My family was from Alabama, and I had lived on military bases throughout my childhood,” he said. “The culture I grew up in was profoundly oriented toward service to country.”

Clements requested to be sent to pilot training and left UCLA with intention of going to Vietnam as soon as he could. While he wanted to serve, he says he didn’t want to kill anyone and was glad to be trained as a C-130 transport pilot rather than a fighter or bomber pilot.

Within months of his arrival in mid-1969, things didn’t quite seem right to Clements. One of his primary missions was to fly planeloads of soldiers around Vietnam. One group, a company of paratroopers, struck up a conversation with him after they noticed his parachutist wings.

“They joked with me that when they landed in Saigon it was only the second time they’d actually landed in a plane,” he said. “There was no one like me in that company of paratroopers. None of them had graduated from college. It was a lot of kids who really had no other options. I started gaining an awareness of who was actually fighting this war.”

His doubts began to build after a conversation with a CIA agent in a bar, who smugly informed him some “diplomats” that Clements had flown into Cambodia weren’t diplomats at all.

“He told me I was incredibly naïve if I believed that,” he said. “He said he had a crew on that plane, and that in six weeks there would be a coup.”

Clements thought back to President Richard Nixon’s televised assertion that there were no U.S. combat troops in Laos, which the young pilot knew was false. As the war metastasized and officials lied, everything he believed about the value of what the United States was doing in Vietnam was crumbling.

“It was such a shock — and this takes me back to how innocent I was at that time — to think the president of the United States would look the camera in the eye and lie to the American public,” he said.

As the CIA man promised, the Cambodian coup went off as planned, and the new leader, Lon Nol, signaled his willingness to accept an incursion of U.S. forces into the country.

“Six weeks later I was flying 10 missions day carrying heavily armed American troops into the Parrot’s Beak” — a part of South Vietnam that jutted into Cambodia, Clements said — “in preparation for the invasion of Cambodia.”

Secretly, Clements was in moral crisis over his participation in the quiet but relentless expansion of the Vietnam War. He’d been ignoring a head cold as he flew, and now he used that as an excuse to avoid flying missions. He applied for and received a week of stateside leave, and when he returned, “I told my commander I’d be willing to serve anywhere else in the Air Force, but I would not fly any more missions in Vietnam.”

The reaction from his commanders was muted, and they advised him to quietly drop his objections. He declined and was sent to an Air Force medical facility for psychological testing. Clements was treated professionally — never feeling he was being singled out for retaliation — but during his time in the hospital his opposition to the war hardened. After eight months he was given medical disability and left the Air Force.

Clements’ rebellion against a war he had earlier supported had forced him out of his planned military career, but his ideals of service were unscathed. Seeking a new outlet, he went to medical school and became a doctor. For the next decade, Clements focused on humanitarian issues and ending the war in El Salvador, where he led a number of Congressional delegations. He was a founding board member of Physicians for Human Rights and represented that group at the presentation of the Nobel Peace Prize to the International Campaign to Ban Landmines in 1997, and continued on to work in other aid organizations. Today he teaches human rights policy at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.

The Vietnam War and the choices he made about it helped make him who he is today, he said.

“The decision I made in Vietnam changed the course of my life entirely,” he said. “It just seemed like a disaster at the time.”

COURTESY OF TOM WEINER

COURTESY OF JOHN SIBLEY BUTLER

COURTESY OF CHARLIE CLEMENTS