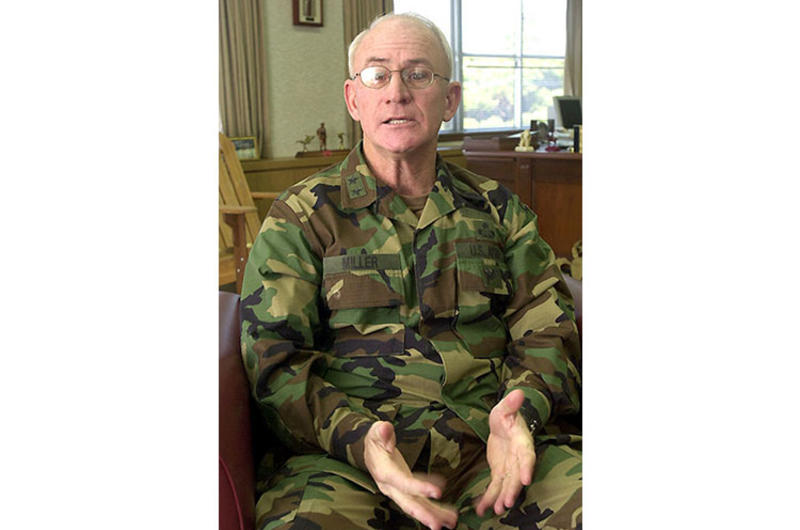

USARJ commander has championed changes in five-year rule, visitation policy

Maj. Gen. Thomas Miller, commander of the U.S. Army in Japan.

By Rick Chernitzer | Stars and Stripes January 1, 2003

CAMP ZAMA, Japan — Change is a natural part of developing and maintaining a ready force, according to the general responsible for the U.S. Army in Japan.

Maj. Gen. Thomas Miller assumed command of Army troops in Japan and Okinawa in August. In his first interview with Stars and Stripes, he said he’s already made some sweeping changes in how the five-year rule, which limits some employees’ overseas employment, is administered locally. He’s also revising the base visitation policy.

“One thing we don’t do, particularly in the military, is … take time to think. We really need to take some time out, sit under the tree and think about whether we’re on the right track,” he said.

The five-year rule, which limits some employees’ overseas employment, “was one of the first things that was brought to my attention,” Miller said. “I had to ask myself, ‘Did we have an equitable and credible way of applying that?’

“In the past, to me, it was somewhat very decentralized. A supervisor could make a decision on a five-year rule on one of his employees. To me, that’s just not right.

“So what I’ve done, which is counter to my leadership style of decentralization, is … actually centralized the decision-making on the five-year rule.”

Miller created a board made up of military and civilian personnel, headed by Col. Joseph Manning, USARJ deputy commander, to make recommendations on five-year rule waiver requests. Miller then makes the final decision.

“What I will look at is exactly the circumstances of that employee, and I will weigh the benefits of that employee and the benefits to this command,” Miller said.

He said his decisions would combine personal issues — such as a child completing school — with operational ones, such as completing a project.

“But there’ll be no old boy network, favoritism, cronyism. I’m trying to remove that,” he said.

An employee who disagrees with Miller’s decision can appeal to him directly. “And I’ve had them do that,” he said. “They usually say, ‘Well, I’d sure like to stay, but I understand.’ It’s a people matter, and it’s very emotional.”

Miller said the policy, which dates to the mid-1960s, is intended to promote fresh ideas, but its execution causes most of the headaches associated with it. The rule applies only to certain types of employees and only at overseas bases.

“I see the logic in what they’re attempting to do,” he said. “But I will be quite frank and say that there are flaws in it. It doesn’t apply to the entire work force. To me, that’s a little bit of a rough spot. You can go to Fort Hood and sit there for 15 years, but you can’t come to Camp Zama and sit here for 15 years. But I think it’s the right thing to do over the long-term. New people are agents of change, and they bring in new ideas.”

Miller said he also just completed “a very extensive reexamination of the entire pass system here.” The system caused some controversy last year after the disclosure that some guests not covered by the status of forces agreement were able to sponsor other non-SOFA guests onto post.

“We’ve metered that down significantly. And right now, non-SOFA personnel cannot sponsor non-SOFA personnel,” he said. “That cannot happen. SOFA personnel can in fact sponsor non-SOFA personnel and we want that, that’s part of being a good community. I want them to come onto this installation and be a part and share. But what we can’t do is let it get loosey-goosey. … By nobody’s fault, things drift. And that one slowly drifted. I just felt that needed to be corralled a little bit.”

SOFA personnel have to meet and escort visitors. Exceptions, he said, are “very minimized.” One example, he said, was admitting the mayor of Sagamihara.

“There is a pass that allows him to get in the rear gate and just go to the golf course. There’ll be other cases, but there are checks made first. There’s a system. We’ll run through the system, we’ll verify with the local police authorities … we’ll do a quasi-background investigation and do a clearinghouse system.”

Miller noted that he grants limited golf course access to the many retired senior Japan Ground Self-Defense Force officers who live nearby. He said they have access only through the rear gate.

“They have a photo ID they’re given. They don’t just come in. The gates also have the ability to double-check if need be,” he said. Miller added that such guests are told “they’re not allowed to just roam around Camp Zama.

“We can trust them and who they are,” he said.

Miller said the people of USARJ “are just phenomenal” but to succeed, they must remain open to reexamining procedures and embracing change.

“You can’t sit here like a potted plant,” he said, “or you’ll become irrelevant real quick.”