Medal of Honor recipient recalls Korean War bayonet attack

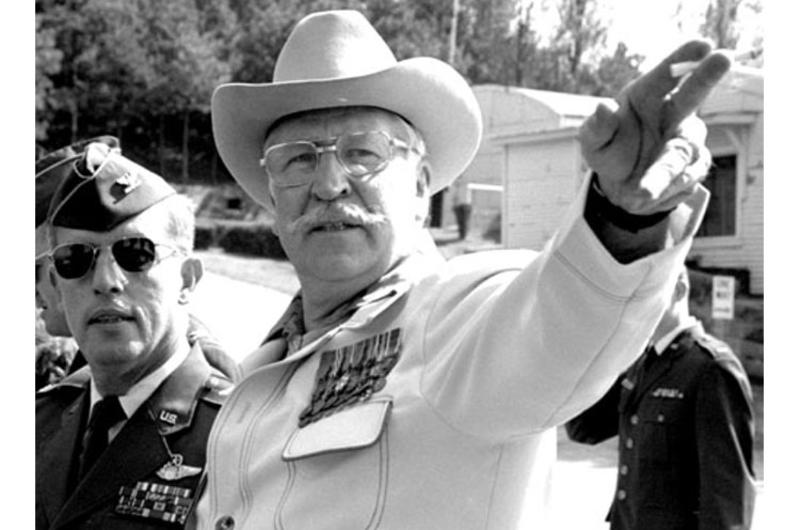

Lewis Millett describes his Korean War experiences during a 1975 visit to Osan Air Base.

By Mike Rush | Stars and Stripes October 13, 1975

OSAN AB, Korea — "I'm proud to be back. I get sentimental, I lost a lot of friends over here, and it brings back bad memories as well as good;" said the tall mustachioed figure with the star-studded pale blue ribbon of the Medal of Honor around his neck as he looked over the area he captured from Communists nearly 25 years ago.

"I can't remember the weather being as nice as it is today," remarked retired Col. Lewis L. Millett, the man who became one of many legends in the Korean War. On Feb. 7, 1951, Millett and his 100-man company took a lofty hill overlooking the flat expanse that now holds Osan AB.

Of the many similar hills and other objectives that United Nations troops seized and held up and down the peninsula, that particular height, known in military parlance as "Hill 180," fell from Communist control in a unique manner.

Millett, then a captain in command of E Co., 27th Inf. Regt. — the "Wolfhounds" — personally led an assault on the hill — with bayonets. That mode of fighting had hardly been heard of in American military circles since World War I when Marines earned the name "Devil Dogs" as a result of their fearsome charges at St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne sector more than 30 years before.

The command "Fix Bayonets" had been almost forgotten since then, but not by Millett. He and his company were on a line of smaller hills south of Hill 180. They were one of several units in "Operation Killer," he explained as he surveyed the site of his battle, an event that won him the Medal of Honor.

Part of "Killer" was a series of attacks on smaller enemy strongholds" during daylight hours, he added.

"I guess I'm a chauvinist," Millett said as he explained why he ordered and led a bayonet attack on North Korean troops entrenched on the hill.

"The Chinese had put out the word that we were afraid of bayonets.

"'Americans afraid of bayonets' is just ridiculous, I thought, so I intended to prove a point."

He did just that three times as his company approached Hill 180. The first attack, he recalled, on Feb. 4 and 5 threw the defending North Koreans back each time.

The third attack, on Feb. 7, started out with a march of about 2,000 yards from a line of smaller hills. Showered with Communist machine gun and antitank "buffalo gun" fire, his men advanced to a point where Millett halted to rally one of his platoons that was receiving heavy fire.

"I stopped them momentarily to put the bayonet on my rifle."

He recalled.

"I said 'fix bayonets and follow me'."

Push up toward the Hill Easy Co. did, goaded on by Millett's shouts of "Grenades and cold steel!" Once close enough to make out emplacements on the hillside, Millett saw the antitank gun nest and rushed it himself, killing the three-man gun crew with his own bayonet, silencing the gun.

The battle that followed on the hillside saw Millett waving his rifle overhead as his men followed up, exchanging rifle shots and bayonet jabs with the Communist troops until they were driven from the hill. Of the 47 North Korean and Chinese dead, 18 fell to the bayonets of Millett and his men of Easy Co.

The company suffered nine killed in the battle, all in a squad on the extreme right flank during the attack, he said.

"They were very dedicated, but they had one-track minds," the Maine-stater-turned-Texan said of his adversaries of nearly a quarter-century ago. "If they were told to do something and there was a change in plans, they didn't react like we would," he said, explaining that after the commander of the Communist force on the hill was killed in the attack, they broke contact and left their positions.

Millett and his wife, Winona, spent part of a Sunday afternoon reminiscing as he walked around the hill here, occasionally pausing briefly to point out a position or area that he remembered from war days, the flat paddy fields intertwined with dirt paths appearing as they must have on that February afternoon in 1951.

In Korea for a revisit to his old battle site as part of the Korea Veterans and Korea Tourist Associations' programs, Millett joined 10 other Medal of Honor winners from the United States for observances marking South Korea's recent Armed Forces Day and dedication of the U.S. War Memorial in Korea.

Reflecting on what he saw and heard during those observances, Millett said, "you have to stop and think of the price we paid, but one thing about it, the people here have done something amazing with the bloodshed that happened here 25 years ago.

"They've proven that we were right in coming over here and helping them retain their independence," he continued.

"I was surprised, I never expected it," he said of winning the nation's top award for heroism in combat. "Of course, a lot of real fine people had to die so that a few might get decorated. There's an awful lot of men who lie buried over here, and the only recognition they received was the purple heart."

Millett explained the success of his company in taking the objective, which has since come to be known as "Bayonet Hill," with a long-unused method of battle as due to his "typically American" unit.

"I had a composite unit, from every national group in the United States. We had black, white and brown — I would say typically American — and typically American, they took the objective and typically American, they were very proud after it," he said with an occasional trace of emotion in his voice.

Millett was awarded the Medal of Honor, which he wears along with many other decorations, on July 5, 1951, a year to the day after another American commander, named Smith, and a handful of men known as "Task Force Smith," shed the first American blood in the Korean War on a hill less than five miles north of Bayonet Hill.

Recalling some of the sites he saw here during the war years of misery and desolation, Millett said, "when I come back and see what the South Korean people have done under liberty and freedom, it makes me feel good.

"You realize the sacrifices that some made were not truly in vain and that these are the kind of people we should support and continue to support."

Millett, who retired from active service two years ago, now lives in Merkel, Texas, serving as Justice of the Peace. After he retired, he explained, "I couldn't find a job, so I ran for election and they elected me."

A native of Mechanic Falls, Maine, he said he is known as "the only Damn Yankee in the State of Texas."