History proves war foes' folly, says novelist Webb

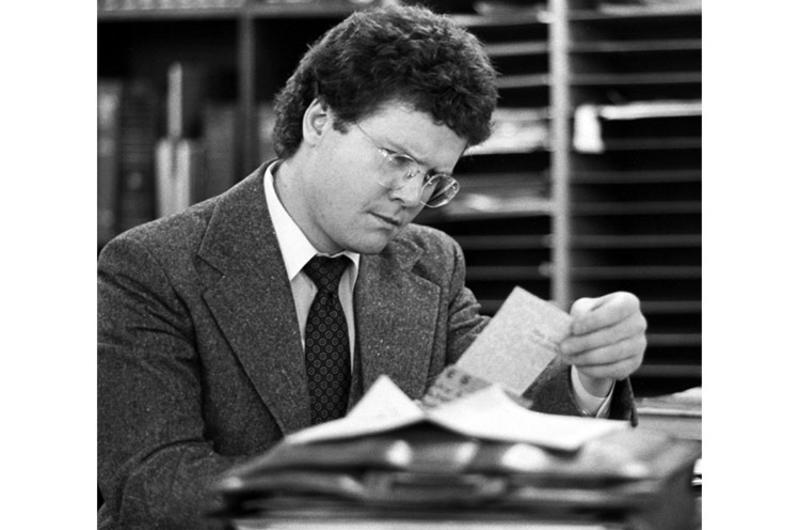

Author James Webb, in the process of writing his third novel, looks through newspaper clippings during a 1983 visit to Tokyo.

By Hal Drake | Stars and Stripes June 7, 1983

TOKYO — Novelist James Webb, whose highly acclaimed "Fields of Fire" refused to apologize for U.S. actions in Vietnam, says history has proven that America's anti-war activists were wrong.

"If I were a leader of the antiwar movement looking back today, I would feel very stupid," Webb said. "You've got two hundred thousand Vietnamese in Cambodia, you've got Russian ports in Vietnam ... everything those people said wasn't going to happen has happened."

He is going to spotlight what he believes is the folly of some of the antiwar leaders in a new novel he is writing.

The only thing he needs to do to make fools of. the likes of Jane Fonda, Jerry Rubin, Dr. Benjamin Spock and others is quote their wartime statements exactly and literally — and that's what he'll be doing in the book.

A lawyer before he turned to writing, Webb believes that history has already indicted those who opposed what he sees as a worthy commitment and a war America should have won.

For that reason, he said, the dispassionate quotes in "A Country Such As This" will be niched beside all that has happened since the North Vietnamese seized Saigon in 1975.

An intense man with the air of a courtroom prosecutor, Webb singled out Spock's 1969 prediction that once the United States got out of Vietnam, the "slaughter" would cease and Southeast Asia would become a tranquil millpond.

As for Fonda's 1972 trip to Hanoi, during which she made propaganda broadcasts for the North Vietnamese, Webb feels she would have faced treason charges in any other war.

"But the only problem in the Vietnam War — William Kunstler would have defended her and she would have turned into a cause celebre, even more than she is now," he said.

Webb said his newest novel, his third, will tell a panoramic story spanning 25 years. It is a kind of latter-day "War and Peace," he said.

With six American characters and a Japanese, "Country" opens during the Korean War and ends in 1976.

The story is not only a tapestry of the Korean and Vietnam wars, but of all the major political and social events of the times — "the extremes of the two philosophies that have been in conflict since World War Two — the left and right, whatever you want to call them — the people who gathered around the Civil Rights movement, antiwar, CIA, Watergate, ERA. It's very concerned about foreign policy and traditional values."

A Virginia mountaineer, Webb had three ancestors at the Battle of King's Mountain in the Revolutionary War and says no American war has passed without a direct-line or remote-branch Webb in uniform — including people on both sides of the Civil War.

Brought up to believe America was worth priming a flintlock or closing a bolt for, Webb graduated from Annapolis in 1968. As a Marine officer, he fought near the Laotian border. He was medically discharged after being wounded twice.

Often feeling more like a defendant than a veteran, Webb was frequently asked after he returned to the United States if he used heroin or considered himself a murderer. These bitter questions stuck in his mind.

He took his degree at Georgetown Law School and worked as minority counselor for the House Veterans Affairs Committee, then wrote "Fields."

Webb's simply told tale of the experiences of a Marine rifle squad in Vietnam offered, right up front, the view that the United States wasn't all wrong in Southeast Asia.

In the book's final scene, a student-veteran is unwillingly dragooned into a campus antiwar rally. He breaks loose to tell demonstrators that they have counterfeit compassion for the suffering Vietnamese and want only to shield themselves from the draft — Webb's own feelings, all the way.

Webb felt that his new work, "Country," had to treat all characters, fictional or factual, with dignity and fairness — left or right, from antiwar sign wavers to a Navy pilot who returned from a North Vietnamese prison to give the book its title-theme quote: "I thank God for a country such as this."

Nevertheless, Webb added, there will be those stigmatizing quotes of the antiwar leaders.

"My feeling is that I believe in accountability," he said. "You said it, you know. You live with it (the quotes). Don't try to tell me something else."

Nor will he go along with the premise that Vietnam is a bad vibe that should be forgotten, swept-under-the-rug history.

"What I care about is America being able to take (accept) that period of time," Webb said. "We've been hesitant to examine that period of history because everyone's nerve-ends are raw. What I've been able to say in this book is OK, nobody's right, nobody's wrong, we're a multicultural society in a continual state of abrasion. We all proceed from different moral reference — that's America ...

"What is wrong and what is harmful is if we just want to push it aside, turn a page without looking at it. Or if we want to say Jerry Rubin's now selling — or whatever he's doing — in New York, and so Jerry Rubin's all right. Well, Jerry Rubin can't deny the harm that he did to us ... for whatever motive. Well, let's just lay this thing out."

The quotes will include excerpts of Fonda's Hanoi broadcasts and some of her statements on American POWs.

"She maintains these guys weren't tortured — and she's such a fool," Webb said. "I have the exact transcript of every broadcast she made and some of those things (she said) are just so foolish."

Much of Webb's novel deals with the POW ordeal. He got the factual goods by gaining the trust of Jeremiah A. Denton and other former captives who made a band-of-brothers pact to keep their experiences in the "Hanoi Hilton" to themselves, not selling out to sensationalists.

As both Capitol Hill lawyer and novelist, Webb has leveled ceaseless fire at the image of the Vietnam veteran as an immoral outlaw with a thirst for blood, feeling this was born of newsmen who wanted to put the American effort in a bad light.

He believes there also are those who carry around with them a heavy burden of guilt for their draft-dodging trips to Canada — the ones who Webb said "for the first time in history committed an antisocial act, and that was turning their backs on their country in a crisis.

"It was very easy in 1968 and 1970 to say you were making a moral statement by doing nothing (spurning military service). But these guys, I think, had a lot of questions about themselves and a lot of guilt — and for years, what they did, they transferred that guilt on the people who served.

"They said, 'If by doing nothing, I've done something that's moral, then you by submitting yourself to this process are at best being used and at worst an immoral animal.' Since 1975, when this stuff turned around (with the human tragedies in Southeast Asia that followed the Communist takeover), these guys are stuck. You only get one chance in your life to respond to that call (for serving your country in a crisis)."

Many of those who ducked the war, Webb said, are now in Congress, Hollywood and the major networks, and he contends they have created a "quiet filter" that has shut out positive images of veterans who served honorably and made good in civilian life.

One network, he charged, made a documentary about veterans in prison and used doctored percentages from a small, three-locale study to state that 34 percent of those who came out of Vietnam were behind bars.

When the legal correspondent of a network approached him for help on a film that would show a different kind of former serviceman, Webb put him in touch with people he had known overseas, some "wonderful upbeat guys" who included a paraplegic. The prospective show was shot down by network executives, Webb said.

"On Veterans Day it was cut because the producer on 'Good Morning America' said it was advocacy journalism," he said. "That's the kind of stuff, that's the subtle filtering, because you take a look at that producer — look at how old he is and see what he did.

"With these guys, it's even more personal. `Wait a minute. I'm 35 years old. I bagged it. You're trying to show these guys as heroes and what does that make me? How's that going to impact on my job and my future?' That's the thinking of these guys and it's so hard to get beyond it."

Another Veterans Day happening sticks in Webb's craw — the opening of the Vietnam War Memorial, not because of the ceremony itself but because of the V shape of the monument. It reminded many veterans of the peace sign of the antiwar protesters.

"A lot of veterans," he said, "call it Jane Fonda's Wall."