As the war rages abroad, counterculture rocks America

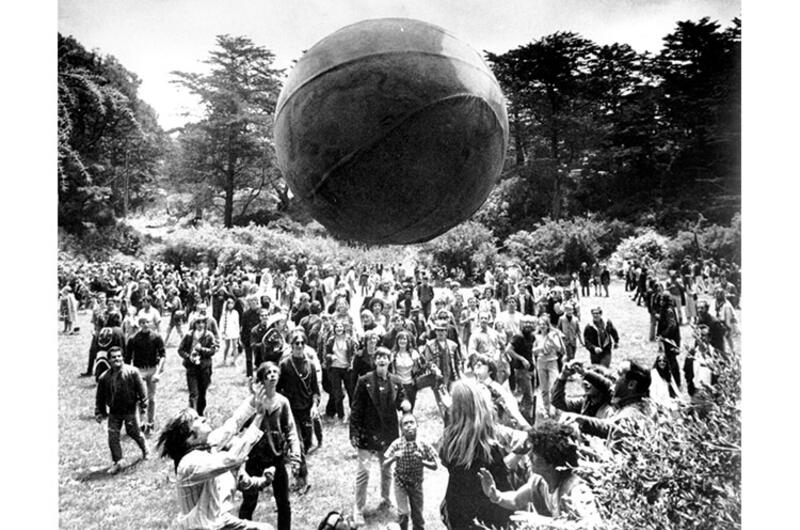

A crowd of hippies keep a large ball, painted to represent a world globe, in the air during a gathering at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, Calif., to celebrate the summer solstice on June 21, 1967, day one of "Summer of Love."

By Travis J. Tritten | Stars and Stripes November 11, 2014

In 1959, “Leave It to Beaver” was in its second season on TV, the first Barbie dolls hit store shelves and Elvis Presley was on the music charts.

Americans returning from World War II and the Korean War had built up a comfortable middle class and moved into the suburbs. It was a time of rigid social rules and faith in authority.

“There was a kind of widespread assumption about the way the world was supposed to work. The people who were in charge were in charge because they knew best,” said David Steigerwald, a history professor who teaches a course on the 1960s at the Ohio State University.

“This is the way people were supposed to live, just by the rules,” he said.

That same year, North Vietnamese communist forces began building the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Southeast Asia. As the conservative decade of the 1950s closed, the United States began its long slide into a bloody and protracted war in far-off Vietnam, a conflict that bitterly divided the nation.

The strict rules and norms that dictated public behavior the decade before — from dress to family to politics — would prove to be a “fragile crust” that was shattered by war in the 60’s and 70’s, Steigerwald said.

The fallout and public disillusionment remains a part of American culture today.

“I would say that the most important thing that it left us with is a corrosive understanding of public life, of the efficacy of government, and I would say of our leadership,” he said.

Television for the first time broadcast the “brutality of war into the comfort of the living room,” as media scholar Marshall McLuhan would later observe in 1975. Images of escalating violence overseas and divisions at home drove many to have deep doubts about the war effort.

At times the country clung to its patriotism. The cultural struggle over Vietnam played out on the radio with the hit song Ballad of the Green Berets and in the theaters with John Wayne waging a righteous battle against the North Vietnamese.

But the tide of public opinion was destined to turn against the war. For the first time in the country’s history, hundreds of thousands of Americans participated in anti-war marches in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere. Musicians and protesters openly mocked the military draft and the president. Abbie Hoffman and other counter-culture figures made a joke of authority.

Troops saw a growing gap between what was happening on the ground and the successes claimed by military leaders and the government. Pentagon documents leaked to the press in 1971 would show that the government had intentionally misled the public about the nature of the war.

“There was a rottenness to the core that was very unsettling for Americans,” said Edward Berkowitz, a professor of history and of public policy and public administration at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

The end of the war became another national trauma — after a history of spectacular successes in war, the U.S. was faced with its first apparent defeat, Berkowitz said.

“It made it look like America was not omnipotent,” he said.

The so-called Vietnam Syndrome would leave the public wary of entering new wars for decades and still echoes in the current war debate and President Barack Obama’s promises of no “boots on the ground” against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, according to Berkowitz.

The public effort to come to terms with the toll and meaning of the war continued in films and books for decades too. A generation after John Wayne was critically panned for his film about Green Berets, Sylvester Stallone would play John Rambo in his Special Forces movie about returning to Vietnam to rescue prisoners of war and right the wrongs of the 1960’s. President Ronald Reagan and a new wave of American conservatism would try to reinvigorate patriotism over the war in Southeast Asia.

But the cynicism for the government and authority that grew out of the war remains the lasting legacy of Vietnam among Baby Boomers and older generations, Steigerwald said.

That has set the war apart from the conflicts that came since.

“I marvel at my students. Most of them have lived the bulk of their lives in a nation at war,” he said. “To some extent, I think they have escaped that inherent cynicism that people in my age group have and I kind of like that about them.”

COURTESY OF JIM THOMS