Too young for Korea, they're real pros now

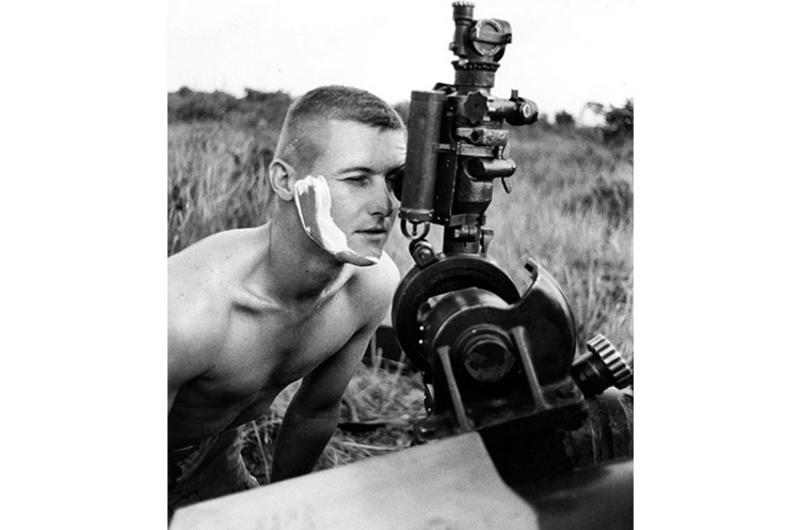

South Vietnam, July, 1965: A fire mission caught Sgt. Homer Charnock of Bravo Battery, 319th Artillery, in the middle of shaving, so he dropped his razor and rushed into position to man his gunsight.

By Hal Drake | Stars and Stripes August 8, 1965

VUNG TAU, Vietnam — Pvt. Bobbie L. Tucker, now an artillery man in Vietnam, can scarcely recall the day in 1953 when an armistice was signed in Korea to end 3½ years of bloody conflict.

Tucker, 21, of Gallatin, Tenn., was only 9 then. Two uncles who had survived the last days of the Korean War often told him about it as he grew up. One used to say: "It was terrible, boy. I sure hope you never have to go to war."

On July 28, 1965, here he was — a young man in another war. He and other young men, the oldest of whom were still in grade school and thrilling to Roy Rogers movies when the Korean War ended, moved 18 105mm howitzers into a grassy valley between Bien Hoa and Vung Tau — a place that looked every bit as bleak and forsaken as the flatlands beneath Korea's Old Baldy and.Heartbreak Ridge.

They were not concerned with a war past, bait with the one at hand. A half hour after midnight — as flares cast a ghostly light over the valley and tracers streaked down a twisting dirt road — the crew of No. 6 gun, Bravo Btry., 319th Arty., moved under the tarpaulin shelter they had put up to protect themselves and their ammunition from the pouring rain. One man turned on a transistor radio.

Through bursts of static, they heard: "Retreat is riot safety ... weakness does not bring peace."

"And no one goes home," a voice resignedly.

Someone else shushed him. President Johnson went on. He told of more troops coming to the Republic of Vietnam, and how the draft was being doubled.

"That's it," a shadowy figure sighed as he switched off the radio. They walked back to the gun. The persistent rumor that the 173d Airborne Brigade (Separate) was returning to Okinawa or the U.S. "in time for Christmas" died an easy death, like many rumors before it.

There was work to do in this deserted valley studded with small bushes, splintered trees and eroded rocks that might have been gravestones. The cannoneers, paratroopers who were all volunteers, had risen from their bunks in distant Bien Hoa at 3 that morning, to spend 3½ hours loading supplies and hitching their guns to trucks before their motor convoy swung out on Highway 15.

A Pacific Stars and Stripes reporter who had been an artilleryman in Korea went along to see if life as a cannoneer was still the same.

It was all the same. Nothing had changed. But it was impossible to find a veteran of the other war and swap memories with him.

The war in Vietnam is in the hands of a new breed.

Sgt. Homer L. Charnock, Wheeling, W. Va., is only 23 — but as No. 6 gun's chief of section, he ably bossed his crew as the convoy moved ponderously and cautiously through small villages draped with faded Republic of Vietnam flags. When the battery moved into the valley and set up the guns, Charnock proved he could be as severe and impatient as any veteran NCO — punishing one man's laxity by making him do 30 pushups.

At nightfall, Charnock called his men together and snapped out instructions. He wanted no smoking, and only limited use of the flashlight on the gunsights and in the ammo pit,

"Now, Charlie Cong is up there, in those mountains. Keep your eyes open "

They did.

They were firing before daybreak. By 8 a.m., one barrage followed another in pumping, slamming unison.

As helicopters loaded with paratroopers dropped behind the mountains to entrap the communists, the cannoneers went right on firing — blasting pinpointed targets a few seconds before the choppers fluttered down.

They were professionals, all of them. Like the young men we had in another war.