By Hal Drake | Stars and Stripes July 13, 1969

They all spoke with the same dry and friendly accent about the same things — the same town, the same high school, the same girls.

One of them turned down a portable phonograph playing Hank Williams' "There'll Be No Teardrops Tonight" and offered an open can of warm beer to a visitor. "Here. We'll make a Kentuckian out of you. Kentuckians drink beer."

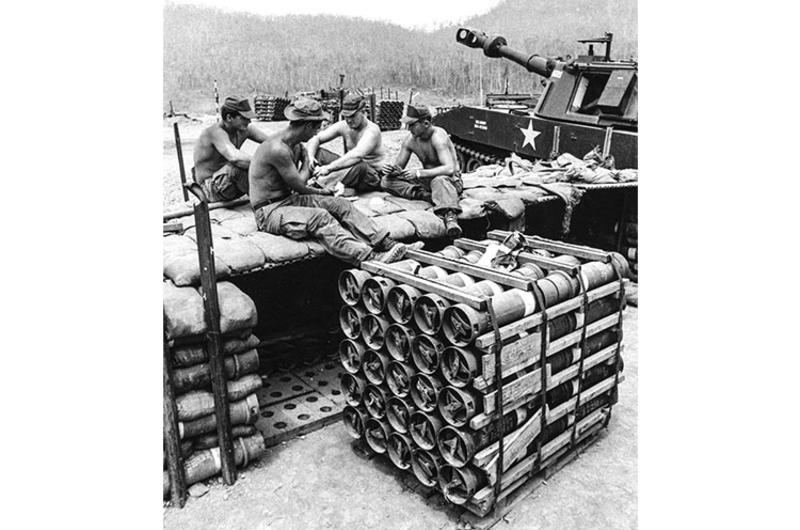

All of the youngsters who sat behind a track-mounted 155mm howitzer — a ponderous machine that resembles a rolling pillbox — were from Carrollton, Ky. A year before, they were working on highways, raising hell at drive-ins and making marriage plans. Then they got the word — by radio, telephone or word of mouth. No more once-a-week meeting at the National Guard Armory in Carrollton, or two weeks at summer camp. This was it; they were in. The 138th Artillery was called up — even if everybody in it had just sweated out the long Pueblo crisis, as their older brothers had once barely cleared the Berlin Blockade.

They were rudely and swiftly dumped into a fourth dimension called Vietnam — and now sat on a mountain that had been beheaded and stripped by bulldozers, an awful place called Fire Support Base Bastogne.

A firebase is a cocked mace of crushing firepower — a compact but powerful concentration of artillery that can throw a heavy package of steel-jacketed explosive in any direction. Below the Kentuckians, a battery of large and deafening 175mm howitzers was making life uncomfortable and perhaps very short for crouching enemy in the A Shau Valley. The smaller guns of the National Guard outfit were spidered in all directions, at the low-lying cowl of thickly-forested mountains around the firebase.

The youngsters from Carrollton had nothing to do; they had not fired since the previous afternoon, when the forward observer saw some figures moving through a nearby treeline. He instantly decided they were not friends oi his. He called back and the artillerymen piled into the hot, narrow, turret-like housing of the gun. For 45 minutes they mechanically hoisted rounds into a yawning breach, then braced and winced as the barrage went out with a loud, heavy sign slam. A treeline ahead was smothered in a leave of dust and flame. They fired 150 times — hard, shirts-off, ear-battering work.

Now — nothing. They only stood and waited to fire. They may fire one round a day or 1,000, depending on which way an unpredictable war might go. It is a formless, directionless war with no fixed lines, firmly secured flanks or pinpointed enemies — a war in which an enemy battalion can suddenly materialize in a thick, empty woods and a decisive, bloodpoker battle can start after two patrols accidentally stumble into each other.

A stuck of canvas-covered ammunition crates became a table for an outdoor hearts game, and a portable phonograph that had traveled 13,500 miles played Hank Williams. They wrote letters and read pocket novels. They talked of the other world they had known.

"I'd just got off construction work on Highway 71," 22-year-old Eddie L. Satchwell recalls. "I pulled into the teen-age center, ready for a good night and a good time. A bunch ran up and said, 'You're activated.' I didn't believe it and told them to knock it off — don't even kid like that. I didn't believe anybody until I went back out to the car and turned on the radio. That was it; before I knew what was happening, I was over here.

"Hell, it's all right. Wasn't as bad as I thought. I'm kind of grateful for it now; I wouldn't have known what any of this stuff was all about if I hadn't come over. It's not so much dangerous up here as it is monotonous."

True enough. The Kentuckians have never seen the face of the enemy — nor even heard the slashing whistle of an incoming round. When they first moved into the firebase five weeks before, astride a footpath that is being widened into a highway, the guns kept up a thunderous, all-hours racket. Cpl. Earl W. Wilson told of the time, "when Charlie was running all over the valley," when the guns poured out 900 rounds in 24 hours — so many that trucks went out on an insecure road, rolling back and forth to the Gia Le Combat Base to keep the smoking howitzer breeches fed. A cease-fire and stand down did not come until 3 a.m.

Now — the young Kentuckians are very good about keeping in touch with their families. Letter writing is a fine way to fill dead time. Even the hearts game takes on a dull, go-through-the-motions monotony,

"Fire mission!" The hearts players stuff their cards in their pockets. Satchwell lays an open pocketbook face down on the canvas. They run to the gun. One round soars out. They walk back. Cards are carefully retrieved from pockets and the game resumes. Satchwell picks up his book. No need to glance at the title; it could be anything from Ernest Ilaycox to Aldous Huxley. It will pass through every hand in the gun section and the firebase until the pages are as thin as ancient parchment and the book falls to pieces. Reading is something to do — even if you only stare blankly at big words.

There they are — a good part of a whole generation in a small town. They are here because they have to be, doing it because it must be done. It is hard to forget any of them — Earl Wilson, Duane Marsh, Wayne Smith, Eddie L. Satchwell.

"They wanted the best Kentucky had," Satchwell grinned, "so they called us."