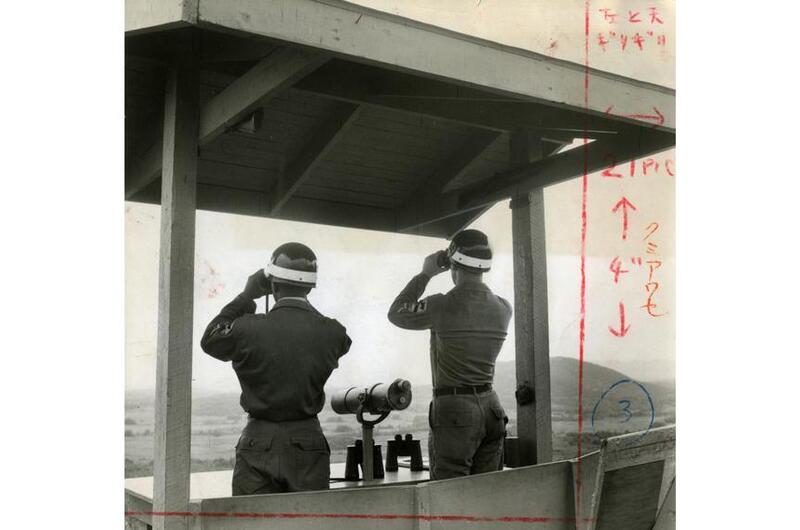

1959: Close Look at the Reds

Two unidentified soldiers check for communist movements across the DMZ in North Korea at Outpost Maizie. OP Maizie was manned by the 1st Reconnaissance Squadron, 9th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division as one of several posts strung across the 18.5 miles of DMZ border.

By Bruce Brugmann | Stars and Stripes March 6, 2024

his article first appeared in the Stars and Stripes Pacific edition, Oct, 1, 1959. It is republished unedited in its original form.

Want to see a real live communist?

The men of Outpost Maizie, on the Demilitarized Zone in Korea, see them all the time. What’s more, they get to show off “their” commies to visitors — such as General L. L. Lemnitzer, Red Skelton, Red Barber, Bob Hope, John Ford, to name a few.

“We can see them out there,” says SP4 Richard Spannagel, 23, who has been manning the post for about 10 months.

“Farmers in the field. Sometimes vehicles on the road. Activity around the bunkers. Just the other day we watched a truck overturn. It took them several hours to get it righted again.”

The VIPs may not always be able to spot a communist through their binoculars, but it is generally agreed that the communists can spot the VIPs.

Briefers tell the story of the north Korean who defected one night in 1955 and told American interrogators that his outpost had detected Secretary of the Army Wilber Brucker through its telescopes one day when he visited Maizie.

Since then, the Red outpost to the left of Maizie has been called “OP Brucker.”

Maizie is manned by the 1st Recon. Sq., 9th Cav., 1st Cav. Div., as one of several posts strung across 18 1/2 miles of DMZ border. Capt. Richard True is the officer-in-charge, and his men are Spannagel, of Unionville, Mich.; PFC Steve Pilhartz, 24, of Cleveland; PFC Adolf Bustamante, 20, of San Bernardino, Cal.; Pvt. Ernest Ward, 19, of Cincinnati; PFC Stanley Siironen, 21, of Duluth, Minn., and PFC William Woods, 17, of Middleboro, Ky.

At least one VIP visits the outpost about once a week. They are usually flown in by helicopter, landing on a chopper pad, on a nearby hill, which is kept as carefully manicured as a golf green.

Cement walks from the mound to Maizie make the inclined trek as easy as possible. Each visitor is given a special card, designed by Capt. Alvin P. Smith, unit adjutant, so the guest can prove that he has actually inspected north Korea from Maizie.

The outpost’s mission, of course, is not so much hosting VIPs as it is to “maintain constant surveillance of communist movements … and give timely warning in the event of an enemy attack.”

In the early evening hours, the watchers hear insect and animal movements that sound much like those they’d hear from a porch in Iowa or Kansas.

Later at night, however, the outpost soldiers report the sounds become more eerie.

“After you’ve been here a while,” says Bustamante, “you learn to tell the sounds of the different animals. There’s the soft whirr of the rabbits, the swifter movements of the deer and the solid crunch of a wild boar. Often, we hear the wildcats yelling. And the bats swooping low. These are the weirdest of all.”

To the right of Maizie lies what was once part of the longest railroad system in the world, before it was damaged. It connected Pusan with railroads all the way across China, Russia, Europe and down into Spain’s Iberian Peninsula.

Behind a hill on the right is Panmunjom, site of the truce negotiations. To the center lies the Kaesong-Seoul corridor, through which Genghis Khan flung his Mongol hordes about 600 years ago. The communists invaded South Korea through this same corridor nine years ago, and some of the conflict’s bitterest fighting took place there.

Kaesong, Korea’s old capital, is barely visible on a good day, and an area of red earth indicates Indian Village, where the prisoners of war were exchanged.

A briefing map, in relief, is tilted in front of a small grandstand, where the visitors are shown these points of interest.

Visibility is often poor, however, and the men say that only about eight nights out of the month allow much sighting through the haze.

Some of the hills bear the legends, in Korean, “Yankees, go home,” picked out in chalky white and almost invisible.

Tacked inside the bunker is a slightly worn cartoon showing a slack-jawed briefer telling his audience:

“… and in this sector the enemy has placed propaganda signs. We’ve been thinking of countering that by putting up Coca-Cola signs.”